Artista lunii aprilie 2022

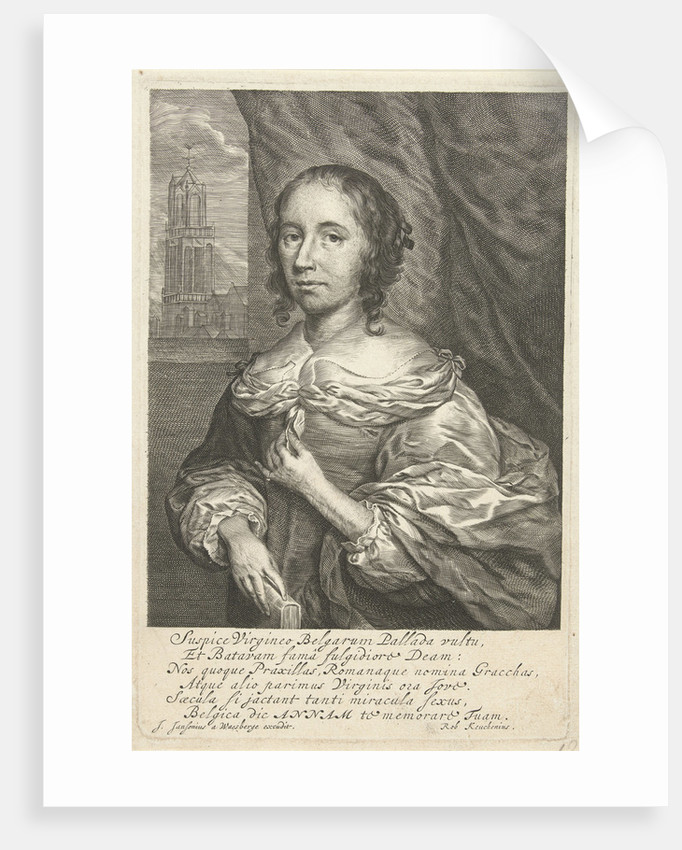

Anna Maria van Schurman (November 5, 1607 - May 4, 1678) was a Dutch painter, engraver, poet, and scholar, who is best known for her exceptional learning and her defense of female education. She was a highly educated woman, who excelled in art, music, and literature, and became proficient in fourteen languages, including Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Aramaic, and Ethiopic, as well as various contemporary European languages.[1] She was the first woman to unofficially study at a Dutch university. Born in Cologne, Germany, in 1607, van Schurman learned to read by age four and later studied Latin, Greek, and several other languages. As the daughter of wealthy parents, she was educated in the humanities alongside her older brothers. Forced to move often to avoid religious intolerance, van Schurman's Protestant family settled in Utrecht in 1623 after her father's death. There, she met poets and philosophers and further cultivated her academic interests.

During the 1630s, van Schurman began corresponding with scholars and philosophers regarding the place of women in academics. She later published dissertations and treatises advocating for the education of women in science and language. However, after becoming a member of the Labadists-a Protestant sectarian community founded by Jean de Labadie, a former Catholic priest-she abandoned her earlier secular interests in science and classic literature. Van Schurman, who never married, remained a member of the group until her death in 1678.

Anna Maria van Schurman is readily considered the most highly educated woman of the 17th century. She questioned the role that women should play in Dutch society, and her determination to receive an education, along with her achievements, made her stand out from other women of her time. Her radical belief that women should be educated to receive an education, not just for a professional purpose or for employment, was controversial and differed from other 17th-century arguments for the education of women. Van Schurman received a strong classical education from her father. Considered a child prodigy, she could freely read and translate both Latin and Greek by the age of seven and had learned German, French, Hebrew, English, Spanish, and Italian by age eleven. She also studied art and became a distinguished artist in the fields of drawing, painting, and etching, though few examples of her art exist today.

At the age of 29, after years of advocating for women's education, van Schurman was invited to attend the University of Utrecht as the first female student. The administration required that she sit behind a curtain in class, as they believed she would distract the male students. She graduated with a degree in law-the first female graduate.

Van Schurman spent much of her adult life writing on the importance of equal education for women, publishing the majority of her works in the 1640s and 50s. In her book Whether the Study of Letters is Fitting for a Christian Woman, published in 1646, she stated that anyone with ability and principles should be allowed to be educated. She believed women should receive an education in all subjects, so long as it did not interfere with their domestic duties.

She actively published articles detailing the ways in which women's brains functioned as effectively as men's and the damage that occurred to women's abilities if they were only considered capable of being wives and mothers. She participated in contemporary intellectual discourse, communicating with important cultural figures, such as the philosopher René Descartes, philosopher Marin Mersenne, and writer Constantin Huygens. Toward the end of her life, she became involved in a contemplative religious sect founded by the Jesuit Jean de Labadie. Labadism was a mystic offshoot of Catholicism that preached the importance of communal property and included the directive to raise children communally. Van Schurman became de Labadie's primary assistant and followed the sect as it traveled. His support enabled her to publish her final book Eucleria, arguably the most thorough explanation of Labadism, in 1673.

Anna van Schurman at The Dinner Party

Anna Maria van Schurman's plate is painted with many thin lines, referencing popular Dutch etchings of the 17th century. Chicago chose an abstracted butterfly form for the plate, a symbol of "Anna's valiant efforts on behalf of women's rights" (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 100).

The colors of the plate, shades of orange, complement the colors of the runner, which is embroidered in a style that was common in 17th-century Holland. Young girls practiced these tiny stitches on samplers, which were meant to teach them the virtues of womanhood, such as docility and obedience. The needlework represents the educational limits of van Schurman's Dutch counterparts (Chicago, Embroidering Our Heritage, 176) and shows how girls were forced to "think small" during this period (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 83). The runner is patterned on early stitch samplers; on the back is an embroidered flower basket, a common motif in Dutch samplers that signified renewal. The rabbit, also a sampler motif, represented timidity. These images of domesticity are offset by the embroidered angels flanking van Schurman's name, which reflect her role as a religious leader.

Van Schurman, in her writings and her life, fought the idea that women should be confined to domesticity. One of her famous quotes is embroidered across the top of the runner: A woman has the same erect countenance as man, the same ideals, the same love of beauty, honor, and truth, the same wish for self-development, and yet she is to be imprisoned in an empty soul of which the very windows are shuttered.

Published writings

The title page and frontispiece of van Schurman's The learned maid, was printed in 1659.

Many of Schurman's writings were published during her lifetime in multiple editions, although some of her writings have been lost. Her most famous book was the Nobiliss. Virginis Annae Mariae a Schurman Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica, Prosaica et Metrica (Minor works in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and French in prose and poetry by the noblest Anne Maria van Schurman). It was published in 1648 by Friedrich Spanheim, professor of theology at Leiden University through the Leiden-based publisher Elzeviers.

Schurman's The Learned Maid or, Whether a Maid may be a Scholar grew out of her correspondence on women's education with theologians and scholars across Europe. In it she advances Jane Grey as an example of the value of female education. Schurman argued that educating women in languages and the Bible would increase their love of God. While an increasing number of royal and wealthy families chose to educate their daughters, girls, and women did not have formal access to education. Schurman argued that "A Maid may be a Scholar... The assertion may be proved both from the property of the form of this subject, or the rational soul: and from the very acts and effects themselves. For it is manifest that Maids do actually learn any arts and science." In arguing that women had rational souls she foreshadowed the Cartesian argument for human reason, underpinning her assertion that women had a right to be educated. Schurman and René Descartes corresponded, and while they disagreed on the interpretation of the Bible they both thought that reason was central to human identity.

When Anna Maria van Schurman demonstrated her artistic talent early on, her father sent her to study with the famous engraver, Magdalena van de Passe, in the 1630s. Her first known engraving was a self-portrait, created in 1633. She found it difficult to depict hands and thus found ways to hide them in all of her self-portraits. In another self-portrait engraving she created in 1640, she included the Latin inscription "Cernitis hic picta nostros in imagine vultus: si negat ars formā[m], gratia vestra dabit." This translates in English to "See my likeness depicted in this portrait: May your favor perfect the work where art has failed."

The Learned Maid included correspondence with the theologian André Rivet. In her correspondence with Rivet, Schurman explained that women such as Marie de Gournay had already proven that man and woman are equal, so she would not "bore her readers with repetition". Like Rivet, Schurman argued in The Learned Maid for education on the basis of moral grounds, because "ignorance and idleness cause vice". But Schurman also took the position that "whoever by nature has a desire for arts and science is suited to arts and science: women have this desire, therefore women are suited to arts and science". However, Schurman did not advocate for universal education or education for women of the lower classes. She took the view that ladies of the upper classes should have access to higher education. Schurman made the point that women could make a valuable contribution to society and argued that it was also necessary for their happiness to study theology, philosophy, and the sciences. In reference to The Learned Maid, Rivet cautioned her in a letter that "although you have shown us this with grace, your persuasions are futile... You may have many admirers, but none of them agree with you."

REFERENCES:

• De Vitae Humanae Termino (medical ethics textbook), 1639.

• The Learned Maid (or Whether a Maid May Be a Scholar or Whether the Study of Letters is Fit for a Christian Woman), 1641.

• Opuscula (correspondence), 1642.

• Eukleria (autobiography), 1673.

• Translations, Editions, and Secondary Sources de Baar, Mirjam, ed. Choosing the Better Part: Anna Maria van Schurman (1607- 1678). Translated from the Dutch by Lynn Richards. Dordrecht and Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995.

• Couchman, Jane, and Ann Crabb, eds. Women's Letters Across Europe, 1400-1700: Form and Persuasion. • Aldershot, UK and Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2005.

• Dykeman, Therese Boos, ed. The Neglected Canon: Nine Women Philosophers, First to the Twentieth Century. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999.

• Irwin, Joyce, ed. Anna Maria van Schurman: Whether a Christian Woman Should Be Educated and Other Writing from Her Intellectual Circle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

• Kersey, Ethel M. Women Philosophers: A Bio-Critical SourceBook. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989.

• Wilson, Katharina M., and Frank J. Wamke, eds. Women Writers of the Seventeenth Century. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1989.

• Zedler, Beatrice H., trans. The History of Women Philosophers by Gilles Menage (1613-1692). Lanham, Md.: The University Press of America, 1984.

NOTES:

• nmwa.org/

• brooklynmuseum.org/