Rethinking Interdisciplinary Public Intellectualism in the Digital Age: Epistemic Fraud and Authentic Scholarship

In the contemporary intellectual sphere, public discourse frequently suffers from a recurring and deleterious epistemic bias: the transmutation of defined technical terms from academic research into either vaguely pejorative labels or casually instrumentalized rhetorical props. In the absence of epistemological literacy, constructs such as multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity are often perceived by non-specialists as interchangeable, stigmatized, or ornamental, obscuring the taxonomy that underpins these classifications. The critical issue, therefore, is not inherent to interdisciplinarity itself but emerges from the misrepresentations produced by two dominant tendencies within the international intellectual context. On one extreme, a vocal and dismissive skepticism lacking intellectual passion and courage — sustained by persistent misapprehensions regarding the epistemic legitimacy of interdisciplinarity and illustrated in local cultural debates, including recent interventions by Professor Adrian Papahagi — reduces it to a presumed dilution of disciplinary competence while overlooking the role of genuine polymaths and the need for epistemic humility in inquiry. On the opposite, a superficial exaltation of the "interdisciplinary" (e.g. Professor Jordan Peterson on philosophy) operates as an intellectual alibi for the absence of methodological grounding, encouraging various forms of pseudo-intellectualism, dilettantism, and conceptual misuse.

This tendency has become increasingly visible across contemporary communication platforms, where deficiencies in critical thinking, hermeneutic precision, and the core principles of cognitive theory (particularly those involving attention, perception, memory, and inferential reasoning) distort the information-processing models through which technical terminology circulates. Such "interpretive distortions are further conditioned by misapplied conceptual frameworks drawn from the philosophy of mind, as well as by linguistic structures that govern categorization, meaning, and semantic transfer"[1], shaping the ways in which words are understood, reinterpreted, and, all too often, miscommunicated. Between these poles — misunderstanding on one side, aestheticized intellectualism on the other — the heart of scholarship is obscured: it is not a genuine nurturing of intellectual virtues and disciplined cultural expertise that underpin research in both fields.

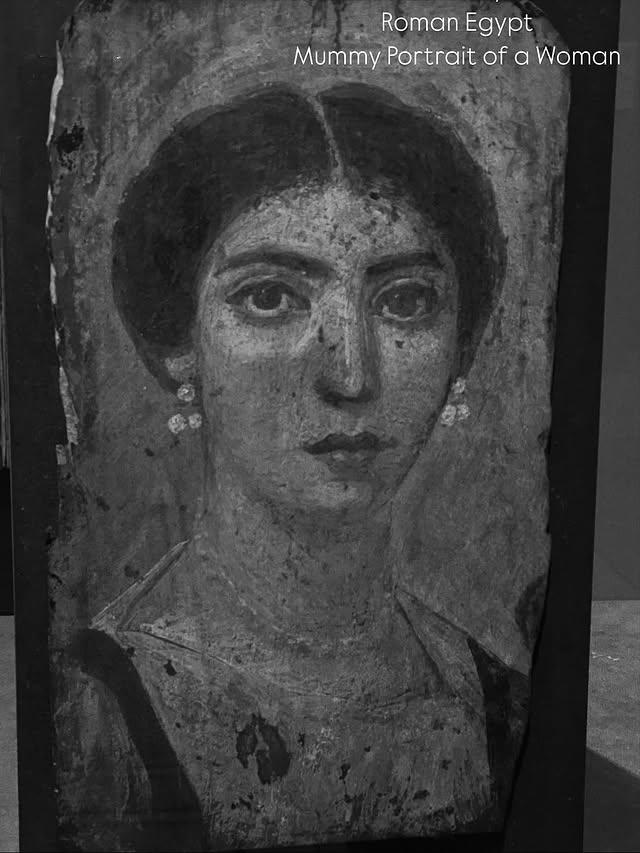

For instance, "academic and scientific modes of inquiry, while both guided by rigor and intellectual integrity, operate according to distinct principles, objectives, and epistemic criteria. Academic texts, particularly within the humanities, follow standards of citation, coherent reasoning, logical argumentation, intertextuality, as seen in philosophical essays, cultural criticism, historical studies, or theological analyses"[2]. Such works are valid even without producing statistical or experimental data, identifying instead critical questions, and interpreting phenomena through hermeneutic, comparative, or symbolic methods. In this context, artifacts, texts, artworks, and historical documents serve as empirical material in a humanistic sense, providing evidence for interpretive analysis rather than for quantitative measurement. "Scientific empirical research, by contrast, relies on systematic, replicable methods designed to generate measurable data, as in experimental psychology, biology, economy or statistical surveys"[3]. Hence, not every academic text is empirical scientific, nor is every philosophical text automatically academic, yet each academic work possesses its own form of validity; the distinction is not hierarchical, but reflects different modes of producing and communicating knowledge, oriented toward particular types of inquiry. Importantly, academic and philosophical scholarship can serve as a foundation for future empirical research. In this sense, academic-humanistic scholarship or humanist scientific texts complements classical scientific approaches, providing insight and conceptual clarity that enable empirical investigations to be meaningfully contextualized and interpreted.

Therefore, a text is not merely a vessel of methodological or empirical correctness, scientific validity, or innovative insight; it must be imagined as a body, as an art form, akin to an illuminated medieval or ancient manuscript. Each sentence, each phrase, each word must possess tone, rhythm, and inflection, infused with artistic vitality, so that the text itself breathes. Dry, formulaic exposition, the hallmark of conventional bureaucratic academic writing, a body without a soul, cannot sustain this life. Thus, words must be sacred instruments, balanced and harmonized, each carrying semantic weight and expressive power, serving simultaneously as conceptual tools and aesthetic markers.

In this paradigm, the text is imbued with its own form of agency: it is magical insofar as the author is attuned to the transcendental. The intellectual must become one with the flow of transcendence, breathing (ruah) it into the work, so that the text itself may exhale and inhabit the reader. Yet autonomy is partial; the text remains inseparable from its creator, a coalescence of authorial intent and emergent intellectual vitality. Properly animated, it generates new ideas, inspiring scholars, students, and readers to create their own beautiful work. It becomes a conduit of pneuma — a living soul of textual inscription — propagating knowledge and reflective imagination through the intellectual cosmos. In this sense, the writer must possess the genius of the underworlds, the capacity to channel profound depth through the human form, so that the texts exude the weight and resonance of the divine, reverberating long after their initial creation.

Chapter I: Epistemic Architectures of Integrative Scholarship

In the post-Humboldtian European university — whether instantiated through the British collegiate tradition or the Franco-Italian paradigm of thematic doctoral schools — interdisciplinarity functions as an epistemic necessity rather than a rhetorical embellishment. Within postdoctoral research cultures, it is structurally imperative, addressing phenomena whose ontological and analytical complexity surpasses the epistemic reach of any singular disciplinary lens. When enacted with solicitude, integrative scholarship does not dilute disciplinary specificity; rather, it amplifies it, producing coordinated frameworks capable of apprehending multilayered, structurally entangled research objects. "Within the humanities, interdisciplinarity is a negotiation between two complementary fidelities: first, fidelity to the conceptual coherence, genealogical depth, and methodological stringency of one's primary field of expertise; and second, fidelity to the object of investigation, whose intelligibility frequently necessitates transdisciplinary mobility, cross-methodological synthesis, and theoretically informed translation across heterogeneous knowledge traditions"[4]. Such work demands not merely familiarity with adjacent literatures but the development of metaconcepts, translational reasoning, and epistemic scaffolding capable of coordinating disparate interpretive procedures without effacing their internal logics. Illustratively, from a Deweyan perspective, "knowledge is not a static repository but a reflective, experimental praxis, enacted through iterative, context-sensitive engagement with lived experience"[5]. Interdisciplinarity, in this sense, traverses well-charted architectures, whereas transdisciplinarity interrogates and reconceptualizes those systems, generating works capable of accommodating discontinuities, conceptual dissonances, and novelties. Only sustained metacognitive vigilance, tempered by epistemic humility and energized by creative-intellectual imagination, preserves the rigor and responsiveness necessary to apprehend the multidimensional complexity of scholarly objects.

Historically, integrative modes of thought find their most compelling exemplars in figures whose work traversed ethical, aesthetic, symbolic, scientific, and metaphysical domains, long before contemporary discourse endowed such practices with the vocabulary of multidisciplinarity. Women who defied disciplinary partitioning and institutional constraints — Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179), Heloïse d'Argenteuil (1101–1164), Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582), Isabella d'Este (1474–1539), and Sofonisba Anguissola (1532–1625) — illustrate how intellectual creativity can flourish even under conditions in which intellectual, political, or spiritual agency was circumscribed. A broader historical perspective reveals that similarly integrative forms of scholarship developed across multiple cultural spheres. "Lubna of Córdoba (927–984 CE), mathematician, poet, calligrapher, palace secretary, and director of the Umayyad royal library under Caliph Al-Hakam II, Spain; Fatima al-Fihri (c.800–c.880), founder of the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and University, and patron of cross-cultural scholarly exchange; Maryam al-Isturlabi (944–867 CE), whose refinements of the astrolabe influenced astronomical practice; and Gārgī Vāchaknavī (c. 800-500 BCE) the ancient Indian philosopher renowned for her metaphysical disputations in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad"[6], exemplify the emergence of intellectually synthetic traditions embedded in varied historical and civilizational contexts. Their contributions show that the impulse toward integrative inquiry has long been a recurrent feature of human intellectual cultures.

Modern philosophical discourse further emphasize the necessity of such epistemic pluralism. Isaiah Berlin's Four Essays on Liberty (1969) and The Crooked Timber of Humanity (1990) articulate the irreducible plurality of human values, demonstrating that no monodisciplinary framework can accommodate the full spectrum of human experience. Paul Ricœur's Temps et récit (1983–1985) elaborates translational and narratological spaces capable of mediating between interpretive idioms while preserving their ontological distinctiveness. Emmanuel Lévinas, in Totalité et Infini (1961), extends this argument into the ethical domain, insisting that the integrity of the Other cannot be reduced to a single epistemic standpoint. Jacques Ellul's La technique ou l'enjeu du siècle (1954) adds a further dimension by showing that socio-technical modernity requires analytic approaches that traverse sociology, theology, and political thought. Together, these thinkers outline the need for epistemic architectures that sustain conceptual plurality while resisting the homogenizing tendencies that obscure nuance and diminish interpretive depth. Giorgio Agamben further deepens this constellation by revealing how modern political and philosophical concepts cannot be understood from within any single disciplinary horizon. In works such as Homo Sacer (1995) and The Kingdom and the Glory (2007), Agamben demonstrates that categories commonly treated as strictly juridical, theological, or philosophical — such as sovereignty, bare life, or economic governance — are in fact hybrid constructs.

Contemporary research programs operationalize these principles. Curricula extending from broad liberal-arts to highly specialized architectures — for example, Aesthetic Cognitivism, Symbolic and Cognitive Aesthetics, or Political-Religious Hermeneutics — exhibit both conceptual coherence and methodological exactitude. Institutions such as CIRSFID at the Università di Bologna, the London Interdisciplinary School, and the American University of Rome cultivate scholars capable of integrating hermeneutic analysis, critical epistemology, curatorial praxis, and advanced interdisciplinary methodology into unified yet flexible intellectual profiles. For illustrative purposes, "fields such as Renaissance studies, in which iconography, political theology, and the social imagination converge, demonstrate how epistemic productivity can arise from disciplined tensions between domains"[7], thereby fulfilling Scruton's conception of understanding as reflective aesthetic praxis and Maritain's insistence that intellectual formation must nurture morally responsible judgment.

Within these structured landscapes, certain analytic constructs have begun to crystallize as useful heuristic instruments. Among them, two concepts — intellectual nationalism and feminism nationalism — serve not as prescriptive ideologies but as interpretive tools that map specific configurations of scholarly activity. Misapplications — such as their appropriation to legitimize partisan or ideological agendas — signal lapses in epistemic rigor rather than defects in the concepts themselves. When approached with methodological care and ethical self-scrutiny, these constructs can instead sustain intellectually and socially constructive aims: supporting gender equity in institutional contexts, encouraging historically grounded national research trajectories, and fostering scholarly networks that are simultaneously rooted in local intellectual cultures and open to global collaboration.

Within this integrative paradigm, the scholar emerges not as a specialist confined to a single epistemic silo but as a thinker capable of synthesizing philosophical analysis, cognitive-symbolic interpretation, art-theoretical reflection, theological insight, and political reasoning into a coherent, dynamic mode of inquiry. As exemplified, "public intellectual engagement, in this tradition, privileges depth, durability, and integrity over the volatility characteristic of contemporary attention economies, recalling the salon's emphasis on sustained discursive cultivation"[8]. Shortly, at its highest point of synthesis, interdisciplinary binds diachronic epistemic coherence with an ethically attuned responsiveness to the digital and symbolic architectures through which knowledge now circulates.

Chapter II: Pneuma and the Conditions of Intellectual Integrity

Where the preceding chapter articulated the parameters within which interdisciplinarity attains fecundity, this chapter probes its obverse dynamics: the disarticulation of normative textual forms and the allure of rhetorical excess. Exempli gratia, prose once attuned by the cadence of continental philosophy increasingly succumbs to semantic volatility; i.e. language, rather than mediating understanding, functions simultaneously as instrument and obstacle; repetition ceases to illuminate, and judgment becomes unanchored. These deformations manifest in the neglect of source verification and the circulation or artificially generated citation — symptomatic of a broader collapse in scholarly literacy. Here, peripheral digressions are misrepresented as synthesis, producing the appearance of integration without structural coherence. Stylistically, metaphor and ornamental phrasing supplant argumentation; ethically, concepts are mobilized as performative embellishments rather than analytic instruments, eroding the scholar's fiduciary responsibility to truth and to the attentive reader. Authentic interdisciplinarity, by contrast, rests on discipline. It begins with a question that genuinely requires multiple fields and proceeds through the careful selection of conceptual tools appropriate to each. It maintains the internal logic of distinct disciplinary perspectives while building interpretive connections that allow for synthesis without erasure. When these principles are ignored, the result is not integration but disarray: disparate materials are arranged as if they constituted a coherent system.

The ramifications of such misalignment are not limited to stylistic lapses. In applied sciences, conceptual confusion has practical consequences: e.g. medicine requires validation of psychological constructs before clinical incorporation; i.e. "the uncritical transplantation of attachment theory, may result into distortions such as social Darwinism or overlook systemic ecological vulnerabilities"[9] In the humanities, misalignment constricts cultural memory and narrows interpretive horizons, creating conditions in which authoritarian paradigms, such as plutocracy, appear plausible. Philosophy — where political foundations and ethical reasoning are tested and refined — suffers most visibly when conceptual tools are misapplied, amplifying societal vulnerabilities and diminishing the scope of reflective deliberation. Accordingly, pseudo-intellectualism functions as a socio-cultural dynamic that facilitates the rise and entrenchment of kakistocracy. In political theory, the concept of kakistocracy — derived from the Greek kakistos (worst) and kratos (rule) — serves to designate forms of governance assessed as systemically corrupt, administratively inept, or normatively degraded.

To illustrate this distinction, "apophatic theology operates through negation, articulating the divine through refusal of positive definition. Absence there is not deficiency but a mode of presence irreducible to discursive categories"[10]. By contrast, "attachment theory describes empirically observable affective patterns and relational structures"[11]. Their compatibility arises only within a phenomenological interspace, where psychology can articulate the affective experiences surrounding absence while theology interprets those experiences within a transcendental horizon. Collapsing these cosmologies into one another constitutes a form of symbolic violence: it imposes uniformity where distinction is essential. The pertinent question is not "What is God according to clinical psychology?" but "How is sacred absence experienced within the affective life of the subject?". In this reframing, the necessity of boundary work becomes apparent: psychology maps affect; theology interprets its meaning.

Chapter III: Public Pseudo-Intellectualism as a Digital Identity Crisis

Building on Chapter II's analysis of disciplinary misalignment and the disarticulation of textual norms, we see these vulnerabilities extend beyond the academy. In the public sphere, analogous dynamics —performative knowledge, epistemic dilution, and ethical disengagement — manifest as "pseudo-intellectualism", particularly within digitally mediated environments. Chapter III therefore examines how these patterns shape contemporary intellectual identities and the fragile terrains they inhabit.

The term "pseudo", derived from Greek, «meaning "false" or "pretended", provides the foundation for understanding pseudo-intellectualism as the adoption of intellectual forms, aesthetics, or postures without the substantive ethical grounding characteristic of genuine inquiry»[12]. It is crucial to distinguish between the phenomenon itself — a structural and behavioral pattern observable across institutions, cultures, and digital ecosystems — and the pejorative labeling of individuals, which often obscures nuance and generates unwarranted moral judgments. Pseudo-intellectualism is neither novel nor historically isolated, emerging repeatedly in contexts of political, economic, or cultural crisis, yet contemporary manifestations are distinguished by their global visibility and scale, amplified by algorithmically structured platforms, enabling a transnational circulation of simulated intellectual aura.

To situate pseudo-intellectualism within a conceptual framework, it is instructive to distinguish it from proximate forms of intellectual conduct: amateurism, characterized by the pursuit of intellectual inquiry, motivated by curiosity or passion without inherent deception; dilettantism, which privileges breadth over depth and performative display over systematic investigation; and fraudulent intellectualism, in which deliberate fabrication of credentials, research, or expertise aims to mislead. Pseudo-intellectualism occupies a liminal space among these categories: some individuals may evolve into disciplined scholars through sustained study and ethical reflection, while others, if left unchecked, gravitate toward fraudulence. This trajectory is shaped not solely by competence but by intertwined moral, ethical, and psychological determinants — including intra-psychic fragilities, narcissistic proclivities, and unassimilated psychodynamic residue. Crucially, the simulation of intellectual labor mobilizes argumentation, rhetorical conventions, and scholarly postures toward non-epistemic ends, producing effects akin to pseudoscience, in which the appearance of exactitude supplants scrutiny.

Historical and institutional contexts have long reinforced these dynamics. Under centralized political regimes, academic structures often valorized titles, publications, and affiliations over substantive mastery, reducing diplomas to instruments of social currency. Such arrangements produced compliant intellectuals, as exemplified by Romania in 1948 and continuing in 2025. Hannah Arendt, in La crise de la culture (Paris: Folio Essais, 2024), provides perhaps the most lucid Western diagnosis of this modern rupture: "the thread of tradition is broken". «Echoing René Char's haunting reflection — "Our inheritance was left to us without a testament" — and Tocqueville's caution that "when the past no longer illuminates the future, the mind walks in darkness", Arendt insists that the loss of tradition is not a mere historical accident but an anthropological catastrophe. When the present is no longer grounded in continuity, it collapses into emptiness; when the future is severed from living memory, it becomes a directionless abstraction. For Arendt, tradition is not immobilization but the very condition of understanding — the chain of meaning through which each generation apprehends the world»[13].

Consequently, «the crisis of tradition inevitably extends into a crisis of education, where the teacher's vocation is to mediate between the old and the new — a task rendered nearly impossible when the past itself is discredited. In this context, "culture" — a term rooted in colere, to cultivate, tend, and preserve — becomes suspect in a mass society that no longer seeks formation but entertainment, reducing the works of the past to consumable objects.»[14]. Arendt thus compels us to recognize that the degradation of contemporary intellectual life is not a superficial phenomenon but the direct consequence of this broken continuity: it is what can be named as the fast-food intellectualism.

In this sense, Henri Pourrat (1887–1959), French writer and ethnologist, in his 1936 work "Toucher Terre" prefigures the demise of world, capturing with attention the texture and rhythms of quotidian life in a society increasingly erased. «Pourrat's call is not to retreat into nostalgia but to recalibrate human existence in accordance with the soil: "It is not a return to the past; it is a return to freshness of the earth". Nature, he argues, constitutes the foundational principle not only of all artistic creation but of life itself. It is in the fields, he observes, that the true conduits of civilization emerge: "All civilization, all taste, all nobility begin and are sustained solely through the fields. From the earth alone comes renewal, order, stylistic refinement, and authentic classicism; one must perpetually return to touch the soil". This principle extends beyond labor to language itself: the idiom, Pourrat insists, is the French language in its most authentic and generative form, the very soil from which strength, clarity, and vitality are drawn. Deeply attuned to the figure of the individual — the cultivator, artisan, sailor, and laborer — he insists that "the person is not the mass; they are men at work, in their fields, at their benches, or in their homes; they are the opposite of the mass". As Bernard Plessy emphasizes in his preface, when a civilization loses the values that once sustained it, when a nation forgets its vocation or descends into misfortune, the path to renewal lies in the perennial virtues of the land, in the ethical and existential rootedness of life. It is from this anchoring in the earth that both individual and collective life may reclaim coherence, integrity, and a sense of enduring purpose»[15].

In a similar manner, Allan Bloom's L'Âme désarmée. Essai sur le déclin de la culture générale (2021), prophetically delineates the decline of general culture within American universities and, more broadly, in the West. «He documents the ascendancy of value relativism that has prevailed on American campuses since the 1960s: the erosion of a classical education in favor of "social issues", the systematic questioning of authority, the simplification of curricula, the introduction of affirmative action, and the dominance of relativism over the pursuit of truth. As Bloom observes, "The purpose of the education they received was not to cultivate cultured young people, but to imbue them with a specific civic—ideological virtue". Bloom incisively characterizes this trend as a transformation of nihilism into moralism. Under the guise of absolute relativism, decadence is propagated through deconstruction, seeking ultimately to dismantle humanity itself by eroding the very conditions of the political sphere: origins, belonging, Greek-style friendship, and the Aristotelian definition of man. In effect, the goal has become to reduce the human being to "a moral animal", preoccupied solely with personal desires and feelings. Tocqueville had already observed this tendency in democratic societies: "In democratic societies, every citizen is usually occupied with the contemplation of a very petty object, himself". Today, this observation is amplified by a heightened indifference to the past and the loss of any national vision for the future. In earlier times, men were members of communities by virtue of a divine order and through close bonds of blood that constituted family. "To preserve their existence and identity, men must love their families and peoples, and maintain loyalty; for one who possesses neither land nor familial traditions will struggle to resist the allure of individualism" and to see oneself as part of a continuum of past and future»[16].

Therefore, contemporary skepticism among younger cohorts — Millennials and Generation Z — reflects "a growing recognition that credentials do not reliably signify expertise"[12], intensified by digital platforms. The performative strategies of pseudo-intellectuals are often manifested in what scholars term epistemic laundering."Obscurantism, conceptual pastiche, and hermeneutic superficiality — invoking thinkers without engaging primary texts — serve to signal credibility, not illuminate understanding"[17]. These behaviors operate within "algorithmically mediated environments that reward affective intensity, absolute statements, and performative authority, producing knowledge pathologies including misinformation loops, authority inflation, and epistemic populism, where every opinion is treated as equivalently valid"[18]. Audiences experience epistemic disorientation, "losing the capacity to distinguish authentic expertise from performance, while credibility inversion privileges charisma over methodological grounding"[19]. "Pseudo-intellectualism is therefore socially co-constructed; it exists not solely in the cognitive dispositions of individuals but in interaction with responsive digital publics that reinforce performative certainty and marginalize reflective hesitation"[20].

Atributional asymmetry, and identity fragility further characterize pseudo-intellectual behavior. "When confronted with critique, performers frequently pathologize interlocutors, moralize the perceived hostility of criticism, or externalize emotional turbulence"[21]. Such tactics instantiate ego-protective projection, adversarial psychologizing, face-saving maneuvers, and defensive attribution error, wherein neutral critique is perceived as existential threat, and ego-syntonic resonance amplifies misinterpretation, producing defensiveness and rhetorical escalation. Therefore, in contemporary digital intellectual ecologies, DARVO dynamics (deny, attack, reverse victim and offender) invert accountability, obscure aggression, and weaken epistemic authority. Shortly, interactions between intellectuals and amaterurs actors are shaped by reputational anxiety, compulsive monitoring, and oscillations between idealization and denigration. "These distortions are often intensified by the instrumentalized abuse of "calling out", strategic name-dropping etc."[22]. Collectively, these processes generate self-reinforcing cycles of projection and moral grandiosity, destabilizing the integrity of public intellectual discourse.

In contrast to performative pseudo-intellectualism — "which confuses noise with thought, acceleration with depth, and abstraction with lucidity"[23] — a lineage of European thought offers a radically different conception of intellectual life. Pierre Hadot (Éloge de la philosophie antique, 1995) emphasizes philosophy as a lived discipline, while Hermann Hesse (Le Loup des steppes, 1927) diagnoses the modern soul as torn between incompatible temporalities, showing how human beings are undone by the very forces they pursue — power, pleasure, materiality, or the frantic liberty of a culture without center.

Collectively, thinkers such as René Guénon (La crise du monde moderne, 1994/2022) and Maurice Barrès (La Terre et les Morts, 2016) extend this reflection, articulating an ethos in which intellectual life is inseparable from measure, rootedness, interiority, and moral gravity. Guénon traces the modern crisis to a humanist reduction that amputated transcendence, relegating consciousness to its lower strata, while Barrès emphasizes that thought must remain anchored in soil, memory, continuity, and the measured realism of lived life. Within this frame, the pseudo-intellectualism examined in this chapter emerges as a symptom of déracinement, a consequence of severed links to principle, place, and vertical meaning. Any remedy lies not in polemic, but in the recovery of form: an intellectual life that binds thought to character, and freedom to the disciplined cultivation of an inner world capable of bearing weight.

CONCLUSION

In the end of our manifesto, this exalted aspiration — to learn to dance in three steps with the art of knowing, for the love of knowing— finds its origin in divinity and returns, cyclically, toward it, in the direction of eternal illumination. For, in its fullness, knowledge is sacred: a form of liberation from the chains of marginal projections. Knowledge, both creative and recreative, despite all the weapons seeking to constrict it, in its essence embodies the model of self-realization evoked by mystics across the world — a disintegration of the egotistical misanthrope, the petty and fearful individual, this poor, vain creature, trembling, struggling toward nowhere. The knowledge of artistic worlds, of the philosophy of art, and of the universe of abstract forms manifests a reflection of the Spirit of the Creator.

Therefore, knowledge unfolds as a tremor in the other, awaiting its crystallization into free will, unbound by any construct of space or time. It is a transcendent ecstasy: movement and rhythm, pause and repose, flux and reflux, a mountain of potency. She is a primordial breath, a majestic and candid goddess, a living exhalation that envelops the earth in its magical plenitude. In its authenticity, knowledge remains a jovial dream of strong Pre-Raphaelite women and sensitive Romantic men. Ultimately, knowledge, as the flower of the desert, a constellation poised in reverie, is mapping our reality.

Thus, the intellectual — the thinker, the scholar, the academic — is, in the end, like the genius woman and her counterpart, united in purpose, serving the light of all. Together, they transmute darkness within darkness, allowing it to become its revelation. In this sacred sphere, the intellectual is at once master and servant: master of their craft, yet servant of the soul of the world — which is the soul of God. They labor not for recognition, but for the ineffable mystery that loves to be loved, for the eternal play of illumination that flows through thought and being. In their devotion, they cultivate knowledge as both movement and stillness, as the refined reflection of the divine within and beyond themselves.

Thus, the scholar is a conduit, a living vessel in which creativity, discipline, and transcendence converge — an alchemist of mind and spirit, transforming words into wisdom.

Bibliography

- Arendt, H. (2024). La crise de la culture. Paris: Folio Essais.

- Barrès, M. (2016). La Terre et les Morts (Carnets de l'Herne). Paris: Carnets de l'Herne.

- Berlin, I. (1990/2013). Four essays on liberty; The crooked timber of humanity. Oxford: Oxford University Press / Pimlico.

- Bloom, A. (2018/2021). L'Âme désarmée. Essai sur le déclin de la culture générale. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan Publishing Co Inc.

- Ellul, J. (1954). La technique ou l'enjeu du siècle. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Frodeman, R. (Ed.). (2017). The Oxford handbook of interdisciplinarity (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Guénon, R. (1994/2022). La crise du monde moderne. Paris: Folio Essais.

- Hadot, P. (1995). Éloge de la philosophie antique. Paris: Albin Michel.

- Hesse, H. (2005). Le Loup des steppes. Paris: Le Livre de Poche.

- Lévinas, E. (1971). Totalité et infini. Paris: Le Livre de Poche, Collection Biblio Essais.

- Maritain, J. (2024). Education at the crossroads. Cluny.

- Pourrat, H. (1999). Toucher terre (La pensée écologique). FeniXX, Sang de la terre.

- Ricœur, P. (1985). Temps et récit (Vols. 1–3). Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

External References

- Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4, Part 2), 1415–1434. https://doi.org/[Link]

- Hastings Cole. (2025, November). The rise of pseudo-intellectualism. Link.

- Unsolicited Advice. (2024, December). The use and misuse of "pseudo-intellectual". Link

Categories: Cultural Criticism, Continental Philosophy, Metaphysics, History of Ideas, Media Studies, Hermeneutics / Epistemology, Sociology of Knowledge, Phenomenology

Genre: Interdisciplinary essay

Reading Level: PhD / Postdoctoral